Wildfire

A wildfire is an unplanned, unwanted wildland fire. Wildfires include unauthorized human-caused fires, escaped wildland fire use events (where appropriate management response to naturally-ignited wildland fires escape), escaped prescribed fire projects, and all other wildland fires where the objective is to put the fire out (Wildfire Hazard Risk Report). While this section’s emphasis is on wildfires as an unwanted hazard, it also discusses wildfire in the context of how and why wildland fires occur.

A wildland fire is any non-structure fire that occurs in areas of vegetation or natural fuels, and can be either prescribed fire or wildfire. Wildland fire occurs when vegetation, or “fuel,” such as grass, leaf litter, trees, or shrubs, is exposed to an ignition source and the conditions for combustion are met, resulting in fire growth and spread through adjacent combustible material. Wildland fires are either ignited by lightning or by some consequence of human activity. In Colorado, lightning accounts for only 17 percent of wildfires, with human ignitions accounting for the remainder (Colorado Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan). Human causes vary and can include escaped debris pile burning, campfires, fireworks, construction sparks, downed transmission lines, and arson.

Wildland fires can occur during any time of year. Although there are frequent references to a “fire season,” ignitions are a result of the ability of fuels to support combustion. In addition to an ignition source, the fuel type, amount of fuel, distribution pattern, and moisture content—coupled with weather and topography—will determine the conditions for combustion and resulting fire behavior. Fire behavior characteristics, often referred to as “outputs,” include intensity, residence time (i.e., the time required for the active flame zone to pass a stationary point at the surface of the fuel), rate of spread, ember production, ember transport distance, and fire size. These fire behavior outputs determine the influence the wildfire has on adjacent and surrounding fuels through radiant, convective, and conductive heat.

Wildland fire is a natural ecological disturbance process, and in many cases it is necessary ecosystem health. Historically, "natural" fire varied in size, intensity, and severity, creating a mosaic of native vegetation communities across different landscapes. Multiple fire events will occur over time and the frequency and length of the fire return interval is dependent upon the vegetation type and climatic conditions. This natural variation of fire has declined in North America over the past two centuries due to a number of human influences. These influences have significantly altered the natural fire regime and created extensive areas of homogeneous forests (forests of the same composition including trees of the same age, size, species etc.), causing a significant and widespread change in fire effects and fire’s influence on ecosystems and people.

Wildfires become wildland-urban interface fires when they transition from natural areas of vegetation to a combination of vegetation and the built environment, such as the Waldo Canyon Fire in 2012. Fire Adapted Communities, Waldo Canyon Fire 2012, National Interagency Fire Center Photo Gallery. Kari Greer/US Forest Service

The introduction and increasing growth of development adjacent to and intermixed within the natural vegetation across the landscape poses additional risk to people and property. In the context of wildfire, the combustible components of buildings, infrastructure, and associated accessories make them susceptible to ignition and are also considered fuel for the fire. A fire burning in this situation has transitioned from a wildfire to a wildland-urban interface (WUI) fire, where a combination of vegetation and man-made structures provide fuel for the fire. This situation increases the complexity, cost, and risk of wildfire in Colorado. In most WUI fire situations, fire suppression resources are quickly overwhelmed and multiple structures are lost.

The terms wildfire hazard and wildfire risk are distinctly different. Wildfire hazard refers to the fuels in a given location and represents the intensity with which an area is likely to burn if a fire does occur there. Wildfire risk is the probability and consequence of a wildfire burning in an area (based on the wildfire hazard, potential losses, and weather conditions). Identifying wildfire hazard is an important first step in assessing the risk of wildfires. Wildfire risk assessments can be analyzed on different spatial scales, depending on the intended use of the assessment.

Applicable Planning Tools and Strategies

In addition to the tools and strategies cited below that are included in this guide, landscaping requirements are also important tools for reducing potential risks from wildfire. Landscaping standards often address issues such as plant material selection (e.g., requiring low-water, native vegetation) and the location of new plant materials installed as part of new development.

Addressing Hazards in Plans and Policies

- Comprehensive Plan

- Climate Plan

- Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP)

- Exploratory Scenario Planning

- Hazard Mitigation Plan

- Parks and Open Space Plan

- Pre-disaster Planning

- Resilience Planning

Improving Site Development Standards

Wildfires are distinct from other natural hazards in two ways:

- Wildfire activity is not limited to natural environmental causes (such as earthquakes, tornados, or hurricanes) because ignition can also result from human activity;

- Humans have the ability to significantly reduce wildfire threat by altering, redirecting, or (in some cases) extinguishing a wildfire.

license); Castle Rock Fire, Ketchum,

ID 2007; National Interagency

Fire Center Photo Gallery

Between 2010 and 2014, an average of 1,192 wildland fires, excluding prescribed fires, occurred annually in Colorado. The number of acres can vary greatly; for example, in 2014, a reported 24,949 acres burned throughout the state, while in 2012 a total of 246,445 acres burned due to wildland fires. Annual structural losses across the state also fluctuate. Between 2012 and 2013, more than 1,200 structures were damaged or destroyed by wildfires that swept across the state, resulting in nearly $1 billion in property damage. Other years, however, have reported significantly fewer structural losses and damage.

Wildfire size (reported as acres burned) is not always indicative of its impact. The Royal Gorge Fire that began on June 11, 2013 outside of Cañon City, burned a total area of 3,218 acres and destroyed 90 percent of the Royal Gorge Bridge and Park. The Royal Gorge Bridge itself was relatively unaffected, but 48 of 52 buildings—including the visitor center, Aerial Tram, Incline Railway, and other attractions—were destroyed. Examples like this illustrate the long-lasting impacts that wildfires can have on the local economy and the variety of community values at risk.

CoreLogic, a national provider of financial and property information, estimates that Colorado ranks as one of the leading states across the western United States in terms of residential properties potentially at risk of future wildfire damage. A 2015 report shows that Colorado has nearly 100,000 homes that are either at high or very high risk of wildfire – translating into $28 billion of residential assets exposed to potential future wildfire damage.These trends also reflect a larger pattern associated with increased development in wildfire-prone areas in the West. Community wildfire risk will continue unless more action is taken to reduce and/or mitigate the threat.

A 2015 report shows that Colorado has nearly 100,000 homes that are either at high or very high risk of wildfire – translating into $28 billion of residential assets exposed to potential future wildfire damage.

Other hazards can contribute to the potential for wildfires or can influence wildfire behavior:

- High winds can down power lines (providing an ignition source), and/or result in areas of downed and dead trees (increasing fuel loads); high winds can also produce rapid rates of spread on active fires and increase the distance of ember transport beyond the active fire perimeter.

- Floods, landslides, and avalanches can result in areas of heavy fuel loading.

- Earthquakes can crack gas lines, creating a higher potential for ignition.

- Lightning can ignite fuels, resulting in wildland fires.

- Drought conditions increase wildfire potential by decreasing fuel moisture. Warm winters, hot and dry summers, severe drought, insect and disease infestations, years of fire suppression, and growth in the wildland-urban interface continue to increase wildfire risk and the potential for catastrophic wildfire in Colorado (Colorado Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan).

Wildfires can also contribute to and influence the magnitude of other hazards. Severe wildfire events may leave slopes denuded and hydrophobic. In these cases a single heavy rain event can lead to higher volumes of runoff and correspondingly a higher risk for flash flooding, erosion and deposition, and mud/debris flows.

Wildfire events may also create open slopes through the consumption of mature timber. In some locations where this occurs, this can create new avalanche slide paths, or enlarge existing avalanche slide paths.

In these cases, a single heavy rain event can lead to higher volumes of runoff and correspondingly a higher risk for flash flooding, fluvial hazards such as erosion and deposition, and mud/debris flows.

Generally, wildfire risk is assessed through combining the following:

- Ignition probability

- Fire behavior potential

- Vulnerability of the values at risk to direct fire impingement (convective and radiant heat from the fire front) and indirect ignition (airborne embers transported ahead of the fire perimeter)

Assessment inputs include the appropriate fuel, weather, topography, and values at risk for a given area, as discussed in more detail below.

Assessing wildfire hazard and wildfire risk, including the risk of WUI fires, requires specialized expert knowledge in fire behavior, forest ecology and dynamics, and structure and infrastructure ignition vulnerability. However, land use planners and other non-specialists should work closely with experts to provide input and understand the implications of the risk assessment on local land uses.

Some communities have a dedicated wildfire mitigation specialist on staff that can provide this level of expertise. Other communities may have access to specialized expertise through the local fire authority, district forest service, academic partners, or other local organizations (e.g., nonprofit or research organizations). It is also common for communities to hire external consultants that specialize in this area.

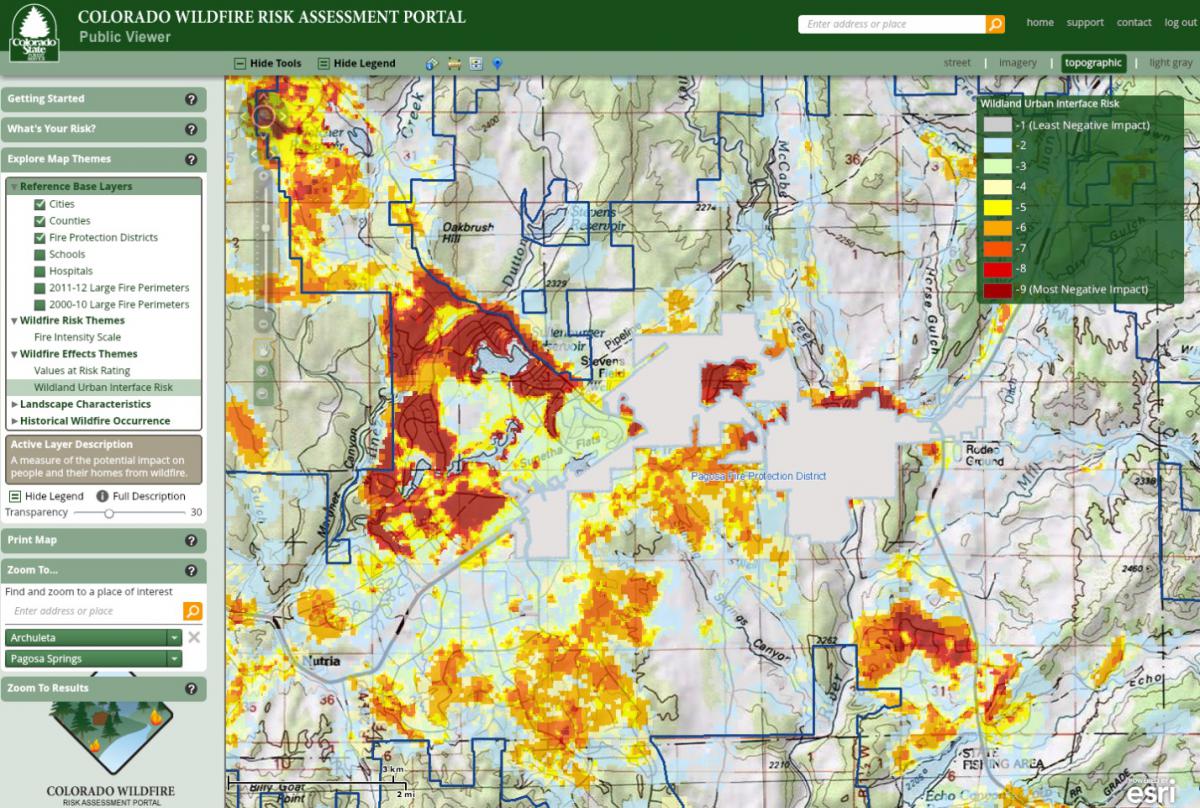

There are a number of wildfire hazard and risk assessment tools available to communities. For those communities with limited capacity or resources, the most accessible tool developed specifically for Colorado is the Colorado Wildfire Risk Viewer on the Colorado Forest Atlas Information Portal.

In addition, there are many widely available guides to help communities develop Community Wildfire Protection Plans, such as Preparing a Community Wildfire Protection Plan: A Handbook for Wildland–Urban Interface Communities (frequently referred to as the CWPP Handbook). These (and similar publications) provide communities with concise, step-by-step approaches for developing a Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP), including a hazard and risk assessment. Summit County is an example of a community that followed the CWPP Handbook guidance for the hazard and risk assessment process in the development of their CWPP. For more information on CWPPs, refer to the tool profile in the main body of the guide.

Finally, some communities elect to work with a consultant that provides a risk assessment based on their own unique proprietary tool. Eagle County, for example, used a proprietary tool that classifies the jurisdiction into “firesheds;” and Glenwood Springs approached their hazard assessment through the use of a proprietary tool that identifies wildfire hazard by evaluating a number of structure loss factors, from immediate hazards near an individual property to proximity area hazards, and then combines these with historical fire occurrence.

Many of these tools are based on models or processes that have difference assumptions, limitations, uses, and scales of use. For example, COWRAP will provide a description of the fire intensity potential based on the conditions within the general vicinity of the location defined by the user. Basic recommendations are also provided for preparedness.

All of the wildfire assessment tools face limitations regarding the accuracy of the inputs. For example, many of the tools rely on a combination of vegetation cover inventory, weather, structure, subdivision, and infrastructure/critical spatial data input. Wildland vegetation, weather and community growth, and layout can be extremely dynamic and in a constant state of change. In many cases, there can be significant challenges in keeping the data inputs that feed these tools updated in order to keep the resulting wildfire hazard and risk assessments accurate. In some cases, this lag can be measured in years. Typically, the more complex the assessment, the more difficult it is to keep up to date; however, if kept updated, the complex assessments become a very powerful tool. Finally, all of the current models are based on past and present conditions, and typically do not predict the future. For the same reasons that make keeping the assessments current a difficult task, using these tools to predict future conditions with any degree of accuracy is extremely challenging. It is important that the user of these tools have the knowledge and expertise to thoroughly understand the inputs, outputs, limitations, and assumptions of all of these tools to ensure they are used accurately and in the most effective manner.

When seeking the professional assistance and advice of a wildfire hazard and risk assessment expert, the planner should look for an individual or team that has advanced knowledge and experience in:

- Wildland fire behavior

- The application of structure ignition concepts

- Wildland fuel model identification and classification

- The assessment of forest and rangeland dynamics and health influence on fire behavior

- Field and model-based wildfire hazard and risk assessment

- The assumptions and limitations of available wildfire assessment tools

- The use and application of spatial applications for wildfire hazard and risk assessment

Non-Specialists and the Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

Wildfire hazard identification and wildfire risk assessments require specialized expert knowledge. Non-specialists, however, play an important role in the process. For example, community planners provide necessary information to help identify community values at risk, planned areas of future growth, key demographic trends, emergency response access and evacuation routes, and other features.

As another example, a public works director can provide information on critical infrastructure and planned capital improvements. By participating in the risk assessment process, non-specialists from other departments and/or agencies contribute knowledge and can better understand how wildfire may potentially affect future community risk.

Colorado communities have access to several sources of wildfire hazard data that are useful for identifying wildfire hazard areas and determining community vulnerability to the hazard.

Colorado State Forest Service (CSFS)

The CSFS is the lead state agency for providing information on wildfire risk and mitigation. The Colorado Wildfire Risk Viewer is the primary mechanism for CSFS to deploy risk information and create awareness about wildfire issues across the state. A public and professional viewer is available online for free (note: anyone can sign up for the professional viewer, which provides additional detail to aid community wildfire planning). CSFS also promotes multiple programs to help reduce wildfire threat, and provides technical assistance to counties, communities, and residents.

Rocky Mountain Insurance Information Association (RMIIA)

RMIIA is a non-profit insurance communications organization representing property and casualty insurers in Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. RMIIA compiles overall estimates of insured losses and number of claims filed for catastrophes (insured natural disasters that cause more than $25 million in damages).

LANDFIRE data

LANDFIRE, Landscape Fire and Resource Management Planning Tools, is a shared program between the wildland fire management programs of the USDA Forest Service and the US Department of the Interior. The website provides free landscape-scale maps and data describing fire recurrence intervals, vegetation, wildland fuel, and fire regimes across the United States. For the advanced wildfire practitioner, LANDFIRE offers fuel model, disturbance, vegetation cover, topography and fire regime data that can be used in conjunction with other inputs (weather, local data) and processed using tools such as ArcFuels, BehavePlus and FlamMap to determine the wildland fire behavior potential and ultimately the wildfire hazard.

Fire-Adapted Communities

A “fire-adapted community” incorporates people, buildings, businesses, infrastructure, cultural resources, and natural areas to prepare for the effects of wildfire. Fire-Adapted Communities also incorporate other programs and tools, such as Community Wildfire Protection Plans (which are covered in this guide), Firewise Communities/USA®, the Fire-Adapted Community Learning Network, and Ready, Set, Go!

National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC)

The NIFC is the nation's support center for wildland firefighting. Eight different agencies and organizations are part of NIFC. Established in 1965 in Boise, Idaho, the center was created as a joint effort by the US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and National Weather Service, among others, to work together to reduce the duplication of services, cut costs, and coordinate national fire planning and operations.

Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control

The Division of Fire Prevention and Control’s mission is to provide leadership and support to Colorado communities in reducing threats to lives, property, and the environment from fire through fire prevention and code enforcement; wildfire preparedness, response, and management; and the training and certification of firefighters.

National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS)

NFIRS provides information on the type and frequency of wildfires that have occurred, including number of wildfires, structure fires, and even other hazard events such as floods, hazardous material spills, etc. Local communities can use the information to help determine risk.