Community Engagement

Community engagement during planning processes offers a venue for residents, stakeholders, and the public to voice concerns and guide decisions.

Community engagement involves a wide range of demographics in a community, whether in age, race, ethnicity, ability, gender, income-level, etc. Typically, the majority of input during a hazard mitigation planning process comes from stakeholders and technical experts to advise on the complexities of hazards exposures and mitigation projects needed. Engaging the community is a plan requirement, although it is often difficult for planning teams to get meaningful engagement from community members.

Many groups have been historically left out of the planning process, which means their needs, priorities and ideas for improving outcomes are not necessarily reflected. Planning teams should take extra steps to ensure that racial and ethnic minorities, non-English speaking residents, and other socially vulnerable community members have an opportunity to contribute and be informed in a meaningful way. Socially Vulnerable community members refers to populations that may have a more difficult time anticipating, responding to, and recovering from a disaster. Existing systems of inequity due to race, ethnicity, gender, or immigration status, among others, increase the likelihood of social vulnerability. For low-income community members, access to financial resources, the pre-existing strains of poverty, or being a single-parent household, are also limiting factors. Physical accessibility due to ability level, as well as, health factors contribute to a person's vulnerability (i.e. elderly and persons with disabilities). Residents that are often hit the hardest by disasters are those most vulnerable and least likely to be involved in the planning process. Communities can conduct a social vulnerability analysis, often included in a hazard mitigation plan, to understand where higher percentages of at-risk populations reside.

Community engagement adds an essential locally-grounded data input to holistically plan for the range of issues different populations face. Community engagement provides a space for dialogue about complex and challenging topics. Additionally, listening to community needs and incorporating them into plans is foundational to building trust (Steichenv, Patterson, & Taylor, 2018), a critical resource in times of crisis. Because of this, greater levels of public participation increase plan quality, including among hazard mitigation plans (Lyles, Berke, & Smith 2014; Masterson et al. 2014). Inclusive community engagement also helps educate a community, build buy-in for future investments, and fosters community ownership of the outcomes and strategies for implementation.

When engagement is thorough and robust, it is because the planning staff acted intentionally. As outlined below, there are steps planners should consider to increase the level of engagement.

Step 1: Determine the desired outcomes and goals for engaging the public.

Before you begin, identify what would make an engagement process successful in your community. This is useful because it will assist the planning team by 1) clearly articulating the main issues to share, 2) identifying the various topics you wish to learn from community members that is pertinent for decision making, and 3) documenting targets for a successful engagement approach will allow you to anticipate adjustments in timing and resource allocations. The thoroughness of the planning process depends on the time and resources set aside for engagement. As a rule of thumb, “go slow in order to go fast”. In other words, take time up front to engage the public as a way to speed the decision-making and plan implementation later. To form community engagement goals, a planning team can consider:

- How to engage populations that have been, or could be, severely impacted by hazards

- Who has historically not been involved, but should be, in the planning process?

- How will engagement set the stage to build support for politically sensitive or costly investments that have a great community benefit for reducing exposure to hazard risk?

Example Goal: High risk and socially vulnerable community members will participate in the hazard mitigation planning process. We will allocate the majority of our outreach resources to these community members.

Example Goal: The Spanish speaking community will have an authentic opportunity to be involved in the planning process as a key demographic that lives within the high hazard area. We will have a 20% increase in participation over the last hazard mitigation plan update.

As a planner develops the community engagement strategy, they can use the following level categories to reveal the depth of engagement: informing, consulting, involving, collaborating, or empowering (Arnstein 1969; APA PAS 593; IAP2). Each level of engagement climbs the “ladder of citizen participation” or the extent of community involvement. Planners should also consider the levels of inclusivity. Beyond working with technical experts, the levels of whom to engage include diverse stakeholder groups, the general public, and vulnerable populations.

Step 2: Engaging Stakeholders

First, identify and chart stakeholder groups and individuals who are influencers that will be impacted by the plan. Consider breadth and depth of experience by topic and geographic areas, or neighborhoods, in your community. Note that depending on the type of plan, some influencers may play a bigger role, such as schools, Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters (VOADs), etc. When considering these common stakeholder groups, also think about which ones represent or provide services to vulnerable populations.

Influencers:

- Business leaders, local business owners, large employers

- Associated regional, state, and federal agencies (including the state and federal disaster recovery coordinators)

- Cultural institutions like museums, theaters, and libraries

- Educational entities, schools, colleges and universities

- Nonprofit organizations

- Faith-based organizations

- VOADs (Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters)

- Organized neighborhood groups

Once stakeholders have been invited into the planning process, the planner can use the snowball method (APA PAS 593) by asking stakeholders if there are other key entities that need to be a part of the discussions. The planning team can chart stakeholder contacts and determine gaps based on the previously identified goals in step 1. When involving stakeholder groups, a common practice is to form a working group or committee to guide the development of the plan or contribute to specific components of the plan. The planning team may consider working groups of “executors” and other working groups of “influencers”. There are different philosophies on the most effective size of a working group. The ideal working group size is 8-12 members. Larger communities should consider multiple subcommittees by topic area or interest group. Consider the trade-offs which range from the amount of input and involvement in the plan versus the speed of the planning process. These considerations are important as you set goals for engagement in step 1.

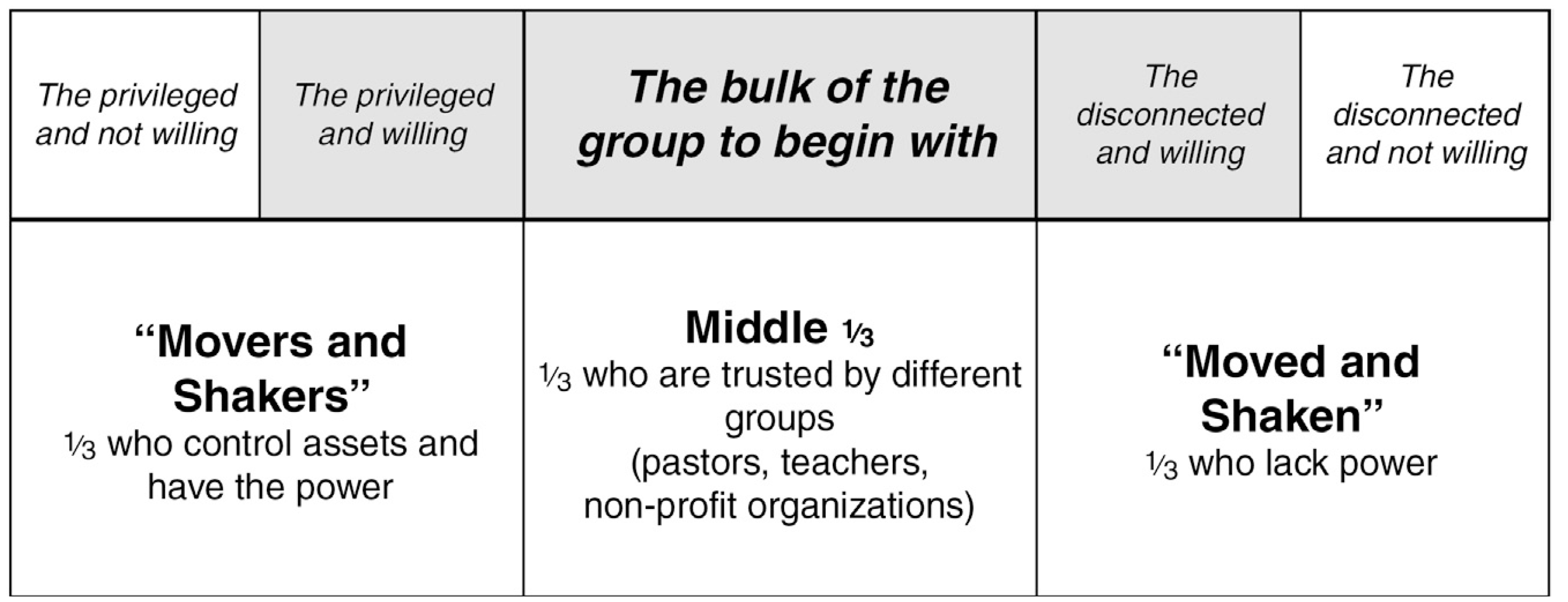

The planning team should also consider the continuum of active and willing partners that exist in the community in order to have a balanced working group. Oftentimes, working groups are made up of the “movers and shakers” or those with more available time, resources, and power. The planning team should intentionally invite stakeholders that represent populations that are “moved and shaken” or those in the community that lack time, resources, and power, but stand to benefit or be negatively affected by the impacts of the plan.

An important way to reach disconnected, but willing stakeholders are through community champions that act as conduits of information to their networks, clients, and constituents. Community champions are trusted leaders and have a track record of tackling issues important to the communities they represent. These stakeholders are relationship brokers to engage hard to reach populations and can foster broader community representation on the working group. They can aid in gathering broader public input, hosting public forums, and connecting with people in the community.

Step 3: Engaging the General Public

The planning team should consider the critical points along the planning process timeline to gather larger public feedback. Make residents known about the planning process and seek their input as early as possible to seed trust. At each interaction, clearly articulate who is inviting them and with what resources, why community input is important, and how the plan could address community concerns.

Determine the methods and approach for engaging the general public. Design the process to provide a variety of ways the public can participate and select the relevant engagement tools such as, large scale public meetings and events, smaller/targeted in-person meetings, focus groups, surveys, questionnaires, forums, virtual engagement tools through social media or paid website options, etc.

Structuring the Invite:

When you are constructing the invitation to contribute to the plan, the invitation should be sincere and should convey:

- Who is inviting them and with what resources

- Why you are asking for their input

- What is possible to accomplish during the meeting

- Who should attend the meeting

- What is required of people who do choose to attend

When engaging people on hazards related topics, it can evoke strong emotions of loss and grief, so compassion is key. Framing the conversation from the beginning by sharing the overall goal with those you are inviting is a strong step towards a productive conversation.

Advertising the Activity:

When conducting outreach and communicating about events or opportunities to participate in the planning process, consider the following avenues:

- City websites or other appropriate websites

- Social media

- Print ads in newspapers

- Local radio or TV spotlights

- Notification on utility statements

- Email lists

- Existing community events

- Existing gathering spaces and meetings (i.e. religious services)

- School sent home notices

- Community notification system

Assembly - Creating the space for engagement:

It is advantageous to host meetings at community-recognized gathering spaces or other well-known venues. When engaging specific populations, consider venues that are familiar to and near your targeted audience. Locations can include community centers, schools, local businesses, religious institutions, etc. Consider limiting meetings at courthouses or other locations that may be perceived as inaccessible or intimidating for your targeted audience. It is important to recognize that some places are traumatic due to some historical event. Seek the advice and counsel of community champions that have this local knowledge.

Choosing how to assemble the meeting room is also very important in establishing the framework above. If planners sit on a dais and lecture to the people, it is hard for citizens to feel like they are equals, whereas a room set up with a number of tables creates small pockets for people to congregate. Again, for hazards conversations, planners should aim to be more collaborative and inclusive than lecturing; they are inviting people into the planning process and are asking for the community’s input. The physical space matters in how people enter the meeting space and participate. Once the group has assembled, it is important to again frame the conversation by sharing goals for the night and what is hoped to be accomplished.

Structure of a meeting:

There are a range of meeting formats that suit different needs. In general, keep meetings to no longer than 1.5 hours and be clear about the time constraints at each point of the agenda. The agenda may be structured in the following way:

- Welcome and introductions- Bring energy. Be positive. Find opportunities for participants to share in a way that reveals common goals and interests (i.e. “I want a safe community”).

- Why they’re here- Explain the project, why it’s important, and why they are critical in the process.

- Activity- Develop an activity that fosters active participation, documents their discussion, and builds commonalities and shared visions between residents. The more hands-on the activity, the better.

- Discussion- Invite participants to share based on the activity. Facilitate a listening session. Mediate conflict points and allow all responses to be heard.

- Wrap up- Take time to reflect and repeat back things you heard during the listening session. Identify next steps and, if applicable, inform participants about additional opportunities to participate in the planning process.

Overcoming Barriers - (APA PAS 593)

If people are absent from the plan making process, it is usually because there is some barrier that is preventing them from having their voice heard. Common barriers include:

- Location- Choose an accessible location for a target demographic and a familiar place (i.e. their church or community center in their community)

- Lack of transportation- Consider meeting locations near public transportation stops.

- Meeting format and Communication- The format should be active where participants feel productive and heard. Use plain language.

- Language and Literacy Barriers- Provide translated materials and hire a translator during the meeting.

- Meeting schedules- Seek input from community champions about the best time for the targeted audience to gather. Provide childcare or children’s activities for meetings held outside of grade-school hours.

- Cost of attendance/Cost of time- Provide food at meetings and childcare options (such a “kids corner”). Consider a stipend or gift card to level off the playing field for low-income and impoverished community members.

- Trust in local government- Work closely with community champions that are trusted among your targeted audience. Ensure they don’t have to provide documentation or personal information to participate.

- Perceived relevance- Clearly articulate in outreach and during the meeting what the plan will do for them and how the plan could address community concerns.

- Creating shared understanding- Be patient when designing the meeting objectives. Allow time when people are processing the types of information and be open to the local knowledge they hold.

Running the public engagement strategy through these filters will allow planners to open up more opportunities for intentional inclusion.

Longmont, CO - Resilience for All: At the end of 2016, the City of Longmont, CO, in collaboration with the Colorado Department of Local Affairs, started their Resilience for All (RFA) program by identifying and eliminating barriers between the Latinx population and local resources provided by the City. The project engaged members from recovery organizations, shelters, city and county employees, faith groups, and other communities in the City to imagine what an inclusive resilient community looks like. From the identified barriers, the RFA program created a list of nine recommendations delivered to the City. This program is a good example of visioning with a diverse community that equipped the City with actionable steps to make the city’s response to hazards more inclusive. The recommendations include:

- Provide the connection, develop guidance, and attempt to alleviate and/or remove the barriers that clients face when accessing services/resources.

- Embrace word of mouth as a trusted source of referral and connection to resources.

- Determine collaboration between department resource agencies. Professionals must work together and streamline the lines of communication that will allow clients to access resources.

- Provide existing bi-lingual emergency resources to all community partners currently working with the multi-cultural organizations.

- Exchange resources with local community organizations that would provide services/resources that general Emergency Services may not provide i.e. legal resources for transgender folks.

- Create a safe [local] neutral point of resource for consumers to formalize complaints.

- Finance nonprofits that focus on outreach teaching English.

- Financially recruit, reward, and retain cultural brokers in local agencies and the community.

- Implement programming such as bi-literacy seal or bilingual pay scales.

- Community engagement expands the data inputs in the planning process. Community input is fine-grained data that is locally grounded which secondary data sources oftentimes does not capture.

- Greater diversity of contributors yields a more holistic understanding of community concerns and viewpoints.

- Community engagement provides a space to dialogue about complex and challenging issues around hazard mitigation.

- Incorporating community needs into plans is foundational to building trust, a critical resource in times of crisis.

- Quality public engagement is also tied to higher public opinion of both the plan and the jurisdiction.

- Greater levels of public participation increase plan quality, including among hazard mitigation plans.

- Inclusive community engagement facilitates educational awareness of hazards.

- Planners are not typically trained in community engagement and may need additional training. Consider taking a class in order to hone skills on facilitation, balancing participation, creating a space where people feel listened to and stay curious about the process.

- Constrained timelines often present during a hazard mitigation plan update process.

- Some communities may lack awareness of the hazard risk. If this is the case, plan for additional meetings or opportunities to engage.

- The technical nature of the subject matter can be difficult for planners to explain without jargon. Take time to consider the language to use and for residents to process and interpret information.

Common Participation and Outreach Elements

- Formal public hearings

- Open meetings

- Workshops or forum

- Call-in hot lines

- Citizen advisory committees

- Household survey

- Interviews with key stakeholders

- Website/internet/email

- Data acquisition and data management

- Brochures or other literature

- Newsletters

- TV/Radio

- Video

- Education and training in several languages

Key Facts

- Administrative Capacity: Planner lead with help from community leaders

- Maintenance: Public engagement plans should be audited every time they are used to ensure inclusivity

- Adoption Required: No

- Associated Costs: Staff time for public outreach activities

Additional Resources

- Community Planning and Capacity Building Recovery Support Function (FEMA)

- In the Eye of the Storm, A People's Guide to Transforming Crisis & Advancing Equity in the Disaster Continuum (NAACP)

- Build a Readiness Kit (Ready.gov)

- Inclusive Scientific Meetings - Where to Start

- Australian Human Rights Commission - Building Social cohesion in our communities

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2)